中国软实力

Chinese Soft Power

In the midst of Donald Trump’s LOOK AT ME!! economic maelstrom, and while he and his chums are presumably making B$B$B$B$Billions from insider trades, the night before last I was watching one of my favourite French political discussion programmes, called C ce soir. I’ve been watching this programme quite religiously since Emmanuel Macron triggered the crazy political crisis in France last summer. I find French political discussion much more lively and interesting than what I get from the BBC and….. forget about any other TV in this country! The French journalists are allowed to have opinions, and they’re allowed to disagree with each other. It’s a bit boring here by comparison.

Two nights ago they were talking about what everyone is talking about now - the US-China superpower showdown, The Rumble until you Bungle, or the Patience of your Working Classes Crumbles. Nobody in Europe is wasting any more energy trying to understand the collective mind of Donald Trump and his lackeys. We’re just more interested in who’s going to win this thing, if anyone. It could even end up being us (I’m European ). Who knows?

The consensus on the panel seemed to be pretty much that Fat Donnie’s strategy, IF that’s the right word, is doomed to fail. The Chinese are ready for him, in all kinds of ways. They do also have their own short-term and long-term economic weaknesses, but they have sufficient belief in themselves and the staying power which the fickle American electorate very obviously does not.

I studied A-level economics at school, and although I didn’t enjoy it all that much, enough of it stuck that I can follow a fair bit of what the experts are saying (the Scottish professor interviewed in this New Yorker podcast breaks it down brilliantly in no more than ten minutes). From the title of this post, however, the reader should gather that I have no intention of talking about economics here. What really grabbed my attention and imagination from the Frenchies’ discussion was a point made by Ali Laïdi, a journalist who works for France 24. China’s major weakness, according to him, is the lack of soft power. Over the following 24 hours I thought quite a lot about what he said.

Before proceeding, I need to say that I’m pretty sure that he was using the term “soft power” to imply only cultural soft power. I don’t think that he was talking about setting up aid, development or infrastructure programmes in Africa, South America or elsewhere. Of course we know the Chinese have been doing that at a tremendous rate, and that it’s all very strategic. Laïdi used the English term in his sentence, which was something like: Les chinois n’ont pas de soft power. Exactly what a French speaker takes that term to mean may differ slightly from what a native speaker understands by it. I’m not entirely sure, but I just wanted to get that out of the way to start with.

Anyone who knows a bit about East Asia should be aware of the fact that China doesn’t really have a lot of friends in the region. They hate the Japanese, for obvious historical reasons. I’ve experienced this on the personal level, in fact. The South Koreans don’t like either the Japanese or the Chinese too much, also for fairly obvious historical reasons. The history of enmity between China and Vietnam goes back centuries, as far as I’m aware (I’ve little to zero knowledge to back up that statement, but that’s my anecdotal understanding). India, notoriously enough, fought a hot war with China in 1962, and the tension on that border remains palpable. The Philipines are in a perpetual state of tension now, with China making unilateral decisions about which seawaters belong to it. The only real “friend” that Xi Jinping has in the neighbourhood is Vladimir Putin, and he’s a “great guy”. We’ve all been through a lot together with him.

It may be interesting to speculate if cultural soft power still matters in the carnivorous geopolitical era that we’re now living through. It wasn’t soft power that enabled Europeans to colonise the world, after all, and it’s effectively a phenomenon which belongs only to the last century or so. Maybe Xi Jinping doesn’t care.

If soft power is still a thing, though, in spite of the fact that Donald Trump et al. are doing everything they can to destroy American soft power, then the United States has a large musical and cinematic catalogue to fall back upon. You don’t have to like it all to recognise that fact. The same applies to my own country. Nigel Farage and Boris Johnson killed our relationship with the rest of Europe for a decade plus, and impoverished us forever; but fortunately one thing that Nigel Farage can’t do is to go back in time to WW2 Liverpool in order to prevent the birth of John Lennon and the rest of the Fab Four. As a result, despite the negative economic consequences of what BrexSHit has done to us, we do retain soft power in the world, thanks to the fact that we’ve created quite a lot of music and other stuff which people like.

So we’ve got the Beatles, the Stones (and don’t forget the KINKS, for God’s sake), Pink Floyd, punk, post-punk, nineties BritPop, the BBC (for all its faults), Doctor Who, Harry Potter, James Bond, the Premier League, and whatever else comes to your mind (probably not the food, I know). The United States have Hollywood, jazz, blues, rock’n’roll, hip-hop, Michael Jordan, the Moon Landings (if you’re OK assuming they weren’t made in Hollywood) popcorn, Hawaiian pizza, Philly cheese-steaks, milkshakes, hamburgers, rodeo shows et al. Of course they can no longer lay claim to being the beacon of democracy in the world at this point, but they will always have the aforementioned. DJT can’t auction all of that shit off for Trump Coin, although he may well try. The pertinent question, then, is what China has to challenge that, if we accept the premise that soft power is still now and always will be something that you really do need to extend an empire in the age of mass media.

I’m not approaching this question from any position of expertise, either in media studies or Sinology but I did live for three years in Japan through the mid-nineties, and I can still read a few characters. That gave me some kind of a broad insight into East Asia, and by extension a very small window into Chinese language and culture. Unfortunately I failed to avail myself of the opportunity to visit China during those three years in Japan. A big regret, but so be it. There were reasons for that, of course. Later, however, I did have quite the encounter with Chinese culture. More on that anon.

Speaking about the question of Chinese soft power to a friend in an Italian restaurant (and that’s a culture with plenty of soft power, innit), I asked him if he could think of any Chinese film which he had ever seen, and which had left an impression on him. He couldn’t think of one, and that was not the case when I asked him the same question about Japan. He immediately started talking about his favourite Kurosawa films. OK, that’s a very highbrow kind of soft power, admittedly, but we could easily enough include Pikachu and other cute cartoon characters on that ledger. I can also mention The Karate Kid, the classic Monkey series from my childhood, the films of Beat Takeshi Kitano (which I LO-O-O-OVE), and we could probably keep listing examples of Japanese soft power for a while.

South Korea has made what I would label a bit of a hostile move onto Japan’s territory over the last two decades, with all this K-pop and K-drama nonsense. In all honesty that’s mostly left me pretty cold. I didn’t at all understand the hype about the Korean film Parasite which won the best film Oscar in 2019, other than that a film which wins the Oscars more often than not wins for some Hollywood-internal-political symbolic reason, rather than anything to do with it being objectively the best film of the year. I could easily name you a hundred non-English language films which at one time or another were more worthy of an Oscar than Parasite was, but never mind - that’s by the by. I know that this K-stuff isn’t targeted at middle-aged men with punk sensibilities, and for all that I do have to congratulate the South Koreans on their pretty successful marketing operation, if nothing else. Given all the shit they’ve been through as a nation over the last 150 years I really don’t begrudge it them in the slightest.

OK, let’s talk about China. Unlike my aforementioned friend, I’ve watched quite a few Chinese films over the years, going back to the eighties, or more likely the early nineties. I think my interest in China came as an extension of the fact that I had studied Russian at school - it would have been the common experience of both cultures under totalitarian Communism that fascinated me - and indeed I did think about studying Chinese at university. In the end, that’s not what I did (see here for what I did in fact study), but I had certainly watched a few Chinese language films several years before I went to Japan. I rather vividly remember watching two of them - Red Sorghum and To Live (full movie available on YouTube apparently!) - in the video library of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, in either 1993 or 1994. Both come from the same director, Zhang Yimou, and both are typical of the films of that period. They look back to explore and celebrate the past which the Cultural Revolution had deplored and attempted to efface, while avoiding the present, always a taboo subject in authoritarian states.

I don’t think I had watched a Japanese film at that particular point, so let’s say that this Chinese soft power got to me before the Japanese did.

Another couple of Chinese films that I saw around that time - and here’s where things get complicated - were The Wedding Banquet and Eat Drink Man Woman. These were the early successes of Ang Lee, who went on a few years later to become very famous as the director of Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, perhaps the most striking example over the last few decades of a film which built some Chinese soft power. I didn’t like it as much as his earlier films, but that’s because I’m weird and I don’t like the stuff that most people do.

You should be expecting a rhetorical catch, and yes, there is one indeed. Many readers will know that Ang Lee is from Taiwan, not Mainland China. I believe that some of the actors in Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon were from the PRC, but that doesn’t change the fact that we must ask ourselves which version of China gets to lay claim to the soft power established by that movie. Pay attention also to the fact that Red Sorghum, for example, was made in 1987, ie before Tiananmen, and that whatever licence directors were being given in the mid-to-late eighties to very tentatively explore a few subjects which had been stamped down by the Cultural Revolution, the events of 1989 made it very clear to all concerned that there were going to be hard limits to that creative freedom.

Let’s proceed a bit further down this avenue. Who is the first person to come to your mind when you think of the whole genre of Chinese Martial Arts movies? Almost certainly it’s going to be either Bruce Lee or Jackie Chan, both of whom were/are from Hong Kong, as is another very important director, Wong Kar Wai, who alongside Ang Lee is the director whose films you’re most likely to have seen if you’ve seen any Chinese-language film at all. Wong’s In the Mood for Love is a beautiful elegaic film which I must confess I didn’t properly understand the first time I watched it. I guess it’s one of those where you have to be well concentrated to follow the story. It’s kind of a common feature of his movies. The earlier Chungking Express, starring the singer Faye Wong, is another one that was hard to follow, but intriguing nonetheless. That doesn’t matter. I’ve made the point, and motivated myself to rewatch both.

(Inserted edit - I just rewatched Chungking Express and it made much more sense. I must have been a bit unfocused the first time, but be in no doubt that it’s not a film that you can follow very casually. It’s very well worth the effort, though. The lady you see in this video is of course Faye Wong, who is also singing the song that you hear.)

I wouldn’t wish to suggest that no great films have been made in Mainland China since 1989. Of course they have, but the most important skill of the director in the PRC is to know how much can be said without bringing down the censor’s axe. To keep the censor away, there seem to be a lot of Chinese films which fall back into ancient history and myth, more often than not with a lot of martial arts thrown in. There’s actually a name for the genre - Wuxia - 武俠, literally martial arts and chivalry - which of course goes back hundreds of years, long before the Lumiere brothers. Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon very much belongs to this genre.

In the spirit of broadening my understanding before publishing this post, I watched another one of these Wuxia films. It’s called Curse of the Golden Flower, and it was directed by the same Zhang Yimou who directed two of the films mentioned earlier. The film was made in 2005, a period when there was much more cooperation between Taiwan and the PRC, and of the three top stars in the film, one (Gong Li) is from the PRC, one (Chow Yun-fat) from Hong Kong and one (Jay Chou) from Taiwan. My understanding is that such cooperation across those difficult straits is much rarer twenty years on.

It may very well be that historical epics like Curse of the Golden Flower contain allusions to the present day which are recognisable to the Chinese viewer but are nevertheless vague enough to be deniable. That must be an interesting subject for those who have the expertise to look for it, but whether or not that’s the case for Curse of the Golden Flower, I have to say that the film left me pretty cold at the end. It’s a blockbuster, with early CGI (I assume), and the settings are lavish, presumably rivalling any Hollywood budget of its time, but ultimately there was something extremely formulaic about the film, and I felt after a while that I could easily enough have been watching a Hollywood epic of the 50s like Spartacus or Ben Hur without any noticeable change of aesthetic.

Sorry for the spoiler, but it wasn’t the first time that I’ve seen Gong Li dishevelled and weeping at the end of a film. I’m not saying that because I necessarily expected a happy Hollywood ending where the good guys win against all odds, but I find something equally clichéed in the ending of this Chinese epic, where the wicked patriarch wins (well, he kind of wins in this film - he wins but he loses), and the message is that, you know, life is sad and we just have to accept it. No, we don’t, and I want to see films where people fight the power more effectively then they do in this film (I never expected the good guys to win), or at least where we see the power right up close, in a form recognisably similar to what we encounter in our own lives. That is to say, I can enjoy these lavish historical dramas now and then for a bit of escapism, but I don’t make them part of my regular cinematic diet.

One film which I really enjoyed, by contrast, is called Beijing Bicycle, made in 2001 (with Taiwanese and French investment). Once again, no big spoilers, but this is much more what I like. It’s a film about normal people’s lives - in this case a story of a kid who comes to Beijing along with millions of others to find work, and gets his bicycle stolen. Lots more than that, of course, but that’s the one sentence synopsis. I have to say that the film felt a lot like a Japanese movie in many ways, a statement which I know a Chinese nationalist (so that’ll be most of them) wouldn’t care for too much. Sorry about that. Maybe it was only because the schoolkids in the film were wearing the type of school uniforms which seem to be very typical across East Asia, and that took me back to Japan.

That’s it on films, for now. Writing this post has made me think that I need to dig a bit deeper, and indeed I do have quite a few more Chinese films queued up now. However, if I try to watch any more of them, I’ll never get round to publishing this post. I will just have to revisit the subject at a later date. The question of Chinese power, hard and soft, isn’t going away. On this inexhaustive and subjective evidence, we can argue that Chinese soft power in cinema certainly doesn’t come exclusively from the Mainland, and indeed that the PRC’s soft power accounts for half of it, possibly at best. This is pretty sad to say, of course, because we are saying that the soft power is being created by 25-30 million Chinese speakers who have been completely or at least mostly free to create whatever inspires them, while 1.4 billion have been muted.

We can now say that the five million or so Hong Kongers are now no longer free to create freely, their rights having been more or less fully eroded since the failed protests against the extradition laws of 2019. The closing off of Hong Kong has in fact been illustrated this week, with a British MP who sits on the Westminster China-scrutiny committee being denied access at the airport in Hong Kong for a personal visit to see her son, who was waiting on the other side. It’s hard to imagine that the whole thing wasn’t premeditated, and it’s clear that Taiwan is now left alone to fly the flag of what China could be. And who knows how much longer?

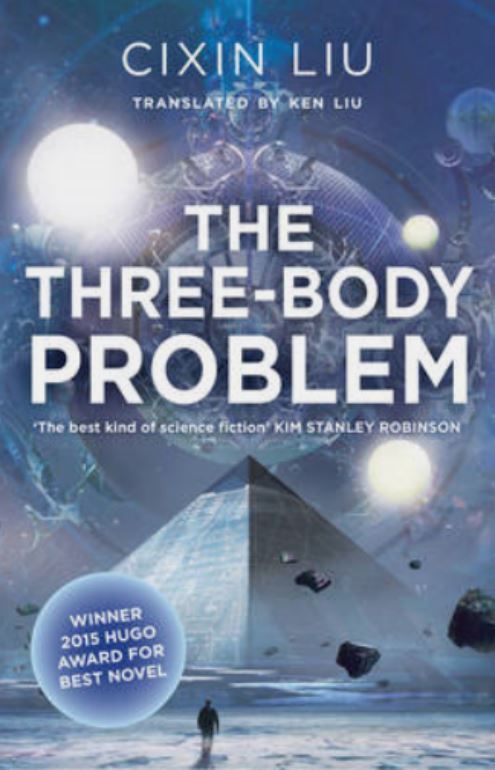

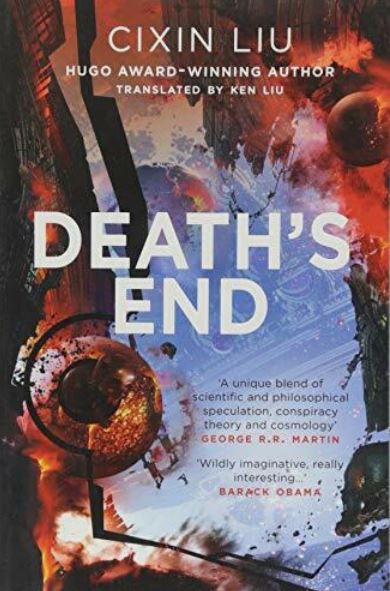

A recent cultural phenomenon coming out of China - Mainland China, in this case - has been The Three Body Problem, which has come to most people’s attention as a Netflix series. It’s actually not such a recent phenomenon if you were a fan of Liu Cixin’s scifi trilogy - Remembrance of Earth’s Past - from the time that the three books were published, between 2006 and 2010 (Three Body Problem was the title of the first book). I have no idea if there’s an intentional allusion in the title of the series to Marcel Proust, but I’d be curious to know. Maybe not. Remembrance of Things Past was a very unfaithful translation of the French original A la recherche du temps perdu (“In search of lost time”).

Finding the Netflix adaptation of The Three Body Problem to be a bit irritating in its facile attempt to coalesce several quite disparate characters from the novels into a cheesy little circle of millenial friends in London and Oxford, I very quickly searched out the Chinese adaptation for a more faithful interpretation of the novels. By an odd coincidence, the two series were made almost simultaneously - interesting to wonder if they were conscious of each other while they were being made.

Watching the Chinese series was a pretty interesting experience. It’s a very long series - probably a bit too long, in fact, while the Netflix version is absurdly abbreviated. Still, it’s faithful to the first novel almost to a fault.

My obsessive reading around the phenomenon led me to discover that the Netflix series was criticised in China for simplifying or stereotyping the original Chinese characters, but most pointedly for converting them into Western characters. No arguments with that. It’s absolutely the case that the Netflix adaptation reduces the series to something like an extended Black Mirror story (nothing wrong with Black Mirror, but this thing is not Black Mirror). Nevertheless, I would also have to come back around and say that any Chinese critics probably need to reflect that criticism back at their own series, because the caricatures of Western characters in the Chinese series were some of the most amateurish that I’ve ever seen. I can’t blame the Chinese for wanting to get their own back on us for Charlie Chan and Ming the Merciless, but still I found it a bit moronic to hear an American general speaking with an Aussie accent, and a supposedly European general with an American accent. Maybe it was intended to offend, though, precisely as retribution for all that stupid yellow-face stuff. I wouldn’t know.

The only way to get to the bottom of things, after all that, seemed to be that I should go directly to the books themselves. If you’re not a scifi nerd you probably wouldn’t take the journey beyond the Netflix version, but for anyone who’s into scifi these books are quite an experience. I generally try to avoid spoilers when I talk about films, so I’ll hold back similarly from telling the story of this saga. The great scifi writers create a whole universe around themselves. The great Isaac Asimov is of course most famous for coming up with the Three Laws of Robotics, and the greatest innovation of Liu Cixin’s universe is the exploration of multi-dimensional space. It’s rather surprising that Asimov and other greats of the genre never seem to have taken the journey that Liu does. Doctor Who does, of course, explore multi-dimensional space, but it’s done in a very different register from Liu’s works, which are pretty wild, mend-bending stuff. Don’t expect Netflix to convey it! OK, I could be wrong about that, but I definitely wouldn’t hold my breath. I do expect them to dumb it down very considerably. The Chinese series, to its credit, really does make the effort to explore the concepts of n-dimensional space.

Is this Chinese soft power? How many fans of Liu Cixin are there beyond the Middle Kingdom? I guess scifi nerds are a special genus unto themselves, far more likely on average to be male, and you probably can’t compare scifi with music and cinema (of all genres) as a vehicle for soft power. If we can say that science is the theoretical basis of hard power, which seems to be a reasonable assumption, scifi is a hybrid soft-hard/hard-soft power, isn’t it? So I’m inclined to reject (provisionally) Liu Cixin’s works as fully qualifying for the description of Chinese soft power. Does that then mean that we must also reject Asimov, Star Trek, Star Wars and Doctor Who as being representative of Anglo-American soft power? Maybe. In the case of Star Wars, I’d say that it is a rather explicit and often very unsubtle extension of American hard power. Some of the hostile aliens have been rather obvious imitations of nations hostile to the United States - the creepy lizard-like characters at the beginning of The Phantom Menace are the first to come to mind, and I’ll let you figure out who you might or might not be meant to be thinking of. I need to be kinder to Doctor Who, because it’s too close to my heart and it’s been on a very long post-colonial journey. Similarly, Star Trek, albeit created in the Empire, has always had a softer heart.

Plenty to think about there! I feel like I’m writing a rough draft, or a prologue to something that will dig a bit deeper one of these days, but I’m going to wind things up here with something a bit more personal. What is more personal than music, after all?

I had a pretty crazy love affair with a Chinese woman. The song on the right was one of the things that she left me with. She was moody and capricious, and she repeatedly tortured me over the fact that I had previously been married to a Japanese woman (WHAT WAS I SUPPOSED TO DO ABOUT THAT FOR GOD’S SAKE?????), but she was definitely one of the good ones (I’ve had a few bad ‘uns as well!) It’s a pretty crazy thing to get involved with a girl when she happens to be your mum’s lodger, but that’s how it happened! Trust me when I say that nobody was taking advantage of anyone. The thing just HAPPENED one Christmas when I was visiting back home. You don’t plan that stuff. A few years earlier, my mum had had the attic converted into a semi-self-contained space for a lodger, and had accommodated a series of female students from Taiwan. I think that I probably met all of them, but didn’t get to know all of them so well - certainly not the way that I got to know this one! If she had been from Taiwan like all the others, the story would probably have been different, but no - the one that I got involved with had to be from the Mainland, OF COURSE 🙄 I don’t like to make it easy for myself.

(Hello, by the way, Cherry Tan, in the very unlikely event that you ever happen to read this 👋🏽)

Long story short - we had a very intense eight or nine months together, but at the end of that she was going back to China. She back China. That was the PLAN. No way to change the PLAN. My circumstances, doing bit-part jobs for the Green Party (a notoriously bad employer, whose philosophically stated good intentions pave the road to You-Know-Where), weren’t anything that she could stay for. Can’t blame her for that. Hard lesons were learned in subsequent years. After a tearful farewell at Heathrow Airport I got a phone-call not more than half an hour later from one of the worst of the Green Party dementors. What an ironic thing to happen at that moment.

We both knew that there was nothing to be done after that farewell, but we didn’t stop communicating for approximately one whole year. It got more and more depressing, for sure, and there really was nothing to be done about it. The Great Firewall of China was already in operation, so the quality of the calls on Skype was low to zero most of the time. Once I had made one of the biggest mistakes of my life, attempting a primary PGCE (nothing to say about that here - too much trauma), all contact ended. There was a very brief and somewhat mysterious moment about three years later. She turned up again in a few messages, and then disappeared with a suspiciously formal-sounding message. I wonder what happened. No point speculating.

Left with nothing but music to hold onto, I dug a bit. Starting at that Faye Wong song, I tacked in my natural direction, towards the punk and the alternative. The uninitiated reader may consider it unlikely that I found much. Not true - I found something that I would never have imagined possible. P.K.14 - the name stands for Public Kingdom for Teens. They remind me more than anything of Joy Division (or rather, what Joy Division might have become if the fool hadn’t killed himself) Check out this song to the right. I don’t know why the quality of the video above right is so low. I can only assume that it was a deliberate aesthetic choice. I really don’t remember how I found these guys, but this was revelation for me, and the song below was the height of the rapture:

This song - 另一边 The Other Side - is the hardest and yet the tenderest of Chinese soft power in my very personal opinion. It got me through some tough moments. I don’t really know why it does what it does to me, but that’s the soft-hard power of music. The riff at the start feels pretty iconic, and it’s strong enough for me to want to know what he’s talking about (Sprachgesang is very much the P.K.14 style), so here are the lyrics. Or at least, here is someone’s translation of the lyrics, which I’m taking on trust:

另一边 – The Other Side

如果你也曾经穿过

If you have crossed

那道看不见的界限

that invisible border

并且在没有颜色的街道上

and have not been able to find

找不到可以停留的地方

somewhere to stay on the colorless street

请你一定回来告诉我

Please come back and let me know

如果你也曾经在另一边

If you have seen a beauty

看见过一个美丽的人

on the other side

她提取出黑夜的颜色

She extracts the color of night

然后把太阳染成黑色

and dyes the sun black

请你一定回来告诉我

Please come back and let me know

如果你从来没有看见过

If you have never seen

被烟雾笼罩的那道白色的光

the white light surrounded by fog

但是在你有限的记忆中

but in your limited amount of memories

记忆是你唯一可以停留的地方

memory is the only place to stay

请你一定回来告诉我

Please come back and let me know

If the translation is reliable (I can’t say, of course), we can agree that these lyrics are gnomic to say the least. What I read about P.K.14 at the time that I discovered them did indeed state that they keep their lyrics very oblique and ambiguous, to avoid official agro. But I have no doubt that there’s subtext, even from puzzling over this very oblique-looking translation. I had this sense confirmed a few years after Cherry Tan back China, when my mum had a very nice lodger from Taiwan (always Taiwan, apart from the one that I got myself “involved” with :~) This was Sophie - lodger #8, if I’m counting correctly. I told her about P.K.14, played her a few of the songs, and asked her about the lyrics. She told me that they were “very brave”, which was more than enough to understand.

I hadn’t listened to P.K.14 for a while until the last week or two. I found myself wondering the other day what they’ve been up to in the last few years. From what I gathered, they recorded a new album fairly recently, in Berlin. I don’t know if that was always their habit, but I would guess that it could be significant that they weren’t recording in China. I could be wrong about that, though. This recent interview seems to show that these guys are big enough back home to get away with saying things that more or less everyone else in Comrade Xi’s China probably can’t. Well, I guess I’ll just have to go and listen to this album to find out what they’ve been up to.

Before moving onto the other Chinese band that I discovered after Miss Tan’s departure, I would like to gratuitously add one more P.K.14 video to the flow of this post, mainly just because I want to, but also because I think that this video illustrates what I meant when I compared them earlier to Joy Division. The song is from the same album as The Other Side.

And now tell me what’s more powerful - this music or a bunch of ships sailing round Taiwan or Australia? I’d like to hope that the former has a longer shelf life.

OK, last on the agenda. I discovered this band - Duck Fight Goose - a little later than PK14. Once again - not really sure how. Probably via Spotify, and due to the fact that they seem to have completely withdrawn from Spotify a long time ago, I don’t really know what they’ve been up to in recent times. I probably need to withdraw from Spotify myself, in order to find out. Spotify is the insidious demon inside my heart which I hardly know to be there.

First up - this song right here - Glass Walls. It’s from around the same time as the earlier cited PK14 songs. I guess it’s not everyone’s cup of tea, but it has plenty of soft power for me. It probably comes more under art rock than punk-post-punk-whatever, but I don’t care toooooo much about categories. I know what I like.

I remember reading an interview with this band around the time that I discovered them, in which the band leader, Han Han (he seems to act as the spokesman at least) said that you can say whatever you want in China. Well, that was maybe before Comrade Xi took over, so I’m prepared to believe that he genuinely believed what he was saying at the time. I wouldn’t be prepared to believe it now, and I do have to wonder if he would say the same, but I just don’t know enough about what it’s like to live in China under the social credit system. I only have Black Mirror, my imagination, and what I see of the Chinese students that I occasionally get to observe on the Leeds-Manchester train, on which I travel every Saturday.

So…… Does China have soft power? I think that the answer is obvious. Of course China has soft power! Besides everything that I’ve discussed here, there’s 5000+ years of a more or less continuous civilisation, of which we still know disappointingly little in the West. Have a walk around the China section of the British Museum, and there’s no argument about that often quite magical power. However, just as Donald J Trump seems to have effectively zero consciousness about how fast he’s frittering away the USA’s soft power, I don’t feel myself that the Chinese Communist Party has any genuine interest in charming the world. Even if it does show such an interest, I seriously doubt that it will have the aptitude, because we know that it doesn’t wish any of us especially well. On the evidence of these Chinese soldiers (or “mercenaries”) who have recently been turning up in Ukraine, Europe needs to be en garde.

We did a lot of bad things in China, especially perfidious Albion, as we did pretty much everywhere, of course. No doubt about that, and we still have a fair few amends to make. But not by giving up on the good things about European thought - humanism, democracy and universal rights, which, however inconsistently and hypocritically applied over the years, remain nonetheless fundamental to who and what we are. As the United States steps out of the world and ceases to be a serious interlocutor, it’s time for Europe and China - en tant que deux grandes civilisations 作为两大文明 - to have a conversation. I’d be very happy to have a conversation with the kind of Chinese soft power that’s been discussed here, but I’m not sure that Comrade Xi’s gang are up for that.

ADDENDUM: I thought that the last paragraph was a reasonable way to conclude, but I just sent this post to an academic friend, not for peer review, just to share. He’s not the stiff kind of prof who would rather point out a split infinitive or a missing comma than comprehend the overall spirit of what you’re tryin’ to say. In his spare time he moonlights as a DJ - find a few of his mixtapes here. As you can see, heavy on the reggae, and so when he wrote back to let me know that he liked the post I apologised for not having found any Chinese reggae. Seconds later, he came back at me with this:

Well, that’s blown my mind one more time. The story is that this guy, Stephen Cheng, was oringinally from Shanghai, but moved to Hawaii after WW2, presumably to get away from the Civil War. He ended up in New York, where he performed on Broadway. According to what is known about him (read all about it here, if the New Yorker allows you to) this is the only record that he made. More than enough. Many have spilled far more blood and sweat to far less effect, I believe.

I am now tripping on the image of Comrade Xi and Fat Donnie shut up in a small room or a broom cupboard with this track playing on a loop, like in one of those famously inventive frat boy initiation rituals. Who would blink first?